permeable bodies

2019

dyscorpia - future intersections of the body and technology - enterprise square galleries, Edmonton, AB - curated by Marilene Oliver

SCOBY & beeswax

Text about the work printed in the dyscorpia catalogue: Lianne McTavish, University of Alberta

“Exploring an Anatomical Palimpsest”

The intriguing sounds get louder as I move toward the gallery entrance. A scratching noise—is it a scuttling insect?—causes me to hesitate but then a sonorous gong calls me forward, into the space. Once inside, I contemplate an intricately constructed anatomical environment. I look closely at a series of tall, darkly stained maple panels along the back wall. With finely carved lines, they display human bodies, some upright and some upside down, opened to show bones and blood vessels. These dissected figures are accompanied by smaller organs and fanciful plant-like forms. Anatomical silkscreen prints on polycarbonate overlay sections of the large bodies, while laser cut acrylic shapes—a white brain, extended spine, and the capillaries of the lungs—provide thicker accents. Two of the dark panels additionally support colourful video projections; one shows human lungs expanding and contracting with breath, and another portrays a floating, transparent leg. I back up to examine the three dark, relatively small enclosures arranged in front of this active, screen-like wall. With the peaked roofs of simplified Shinto shrines, these shelters are covered with similar imagery: limbs, rib cages, organs. The most substantial architectural form is surrounded by a low, wide platform on which rest more fragments of the body. Molded from wax and other materials, these body parts are placed in patterns that are at once deliberate and mysterious. I walk slowly around the space, recognizing some of the bones, muscles, and tendons but puzzling over others, listening to the eerie soundscape, and watching the videos transform.

Entitled “Evolving Anatomies,” the collaborative installation by Marilène Oliver, Sean Caulfield, and Scott Smallwood provides layers of information about bodies and embodiment. Combining historical representations with modern visualizations of the body, the installation is reminiscent of a palimpsest, a term that usually refers to material on which writing has been effaced to make room for new text even as traces of the original marks remain. Visual palimpsests can be seen on the walls of medieval cathedrals when older paintings that have been updated or censored begin to show through the damaged or thinning portions of later imagery. A similar effect is present in “Evolving Anatomies,” where representations of the body from different centuries coexist with, overlap, and support each other. The large, carved anatomical figures on the back panels stem from the weighty treatise, On the fabric of the human body, first published by the Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius in 1543. The woodcut plates used to create the famously well-illustrated text for Vesalius resurface in the material structures—wooden wall panels, shrines, and platform—that enable his artistic reconstructions of the human body to reappear beneath and alongside modern medical imagery.

The palimpsest layers insist that knowledge of the human body does not increase in a progressive manner, whereby past understandings are corrected and then erased by modern innovations. In “Evolving Anatomies,” the decorated wooden plates are the foundation for subsequent imaging technologies, including later prints as well as the video projections made by reassembling computerized tomography (CT) scans. In many ways, CT technologies continue Vesalius’ efforts to see inside and know the human body directly, albeit by using a revolving x-ray beam to take images from different angles around the body, creating cross-sectional images of the bones, blood vessels, and soft tissues. Despite depending on historical efforts, CT scans differ from Vesalius’ work by revealing the hidden depths of living rather than dead bodies. Vesalius strove to anatomize as many corpses as possible, dismembering and effectively destroying them in the process. Although sometimes identified as the rebellious “father” of modern anatomy who rejected ancient practices, Vesalius was equally indebted to the work of his predecessors. Vesalius followed, for example, the Roman physician Galen’s advice to learn from human flesh rather than textbooks, a process that led the Flemish anatomist to challenge some of Galen’s written arguments. “Evolving Anatomies” shows how anatomical technologies have both persisted and changed over time, suggesting their advantages and disadvantages. While the digitized images of the present are impressively vibrant, they seem disembodied and fleeting in contrast to the solid materiality of earlier representations. There is no simple story of the rejection and subsequent improvement of the past.

A particular figure from Vesalius’ treatise is repeated throughout the installation. Created to demonstrate the blood vessels, the body stands upright as if alive, with arms extended and palms open. This now standardized “anatomical pose” was invented during the sixteenth century to counteract the prevailing assessment of anatomical dissection as a punishing act of butchery. The anatomical pose portrays a human body that welcomes and even desires dissection, offering its interior as a gift to the viewer. This allusion to gift giving recurs throughout “Evolving Anatomies.” The video clips are, for example, constructed from an CT dataset of a full body, known only as “Melanix,” offered online for free downloading. These accessible digital scans enable artists, medical practitioners, and others to learn from and refashion an anonymous human body. Another reference to gift exchange is conveyed by the wax body parts laid out on the wooden platform; purchased in Brazil, they are ex-voto forms regularly left in sacred spaces or near healing waters, by people giving thanks for a cure received. Small wax images of the formerly ill body part, whether eyes, skulls, breasts, or hands, materialize gratitude while documenting a physical cure that resulted from prayers or promises made at a spiritually important site. Like other elements of the installation, these ex-votos have layers of significance, for they also relate to the way in which the installation was collaboratively produced by the three participating artists. Each artist took turns giving their collaborators gifts, including objects, prints, drawings, sounds, and words, which elicited return gifts. This generously interactive process of knowledge production finally resulted in the evocative anatomical environment presented to visitors within the gallery space.

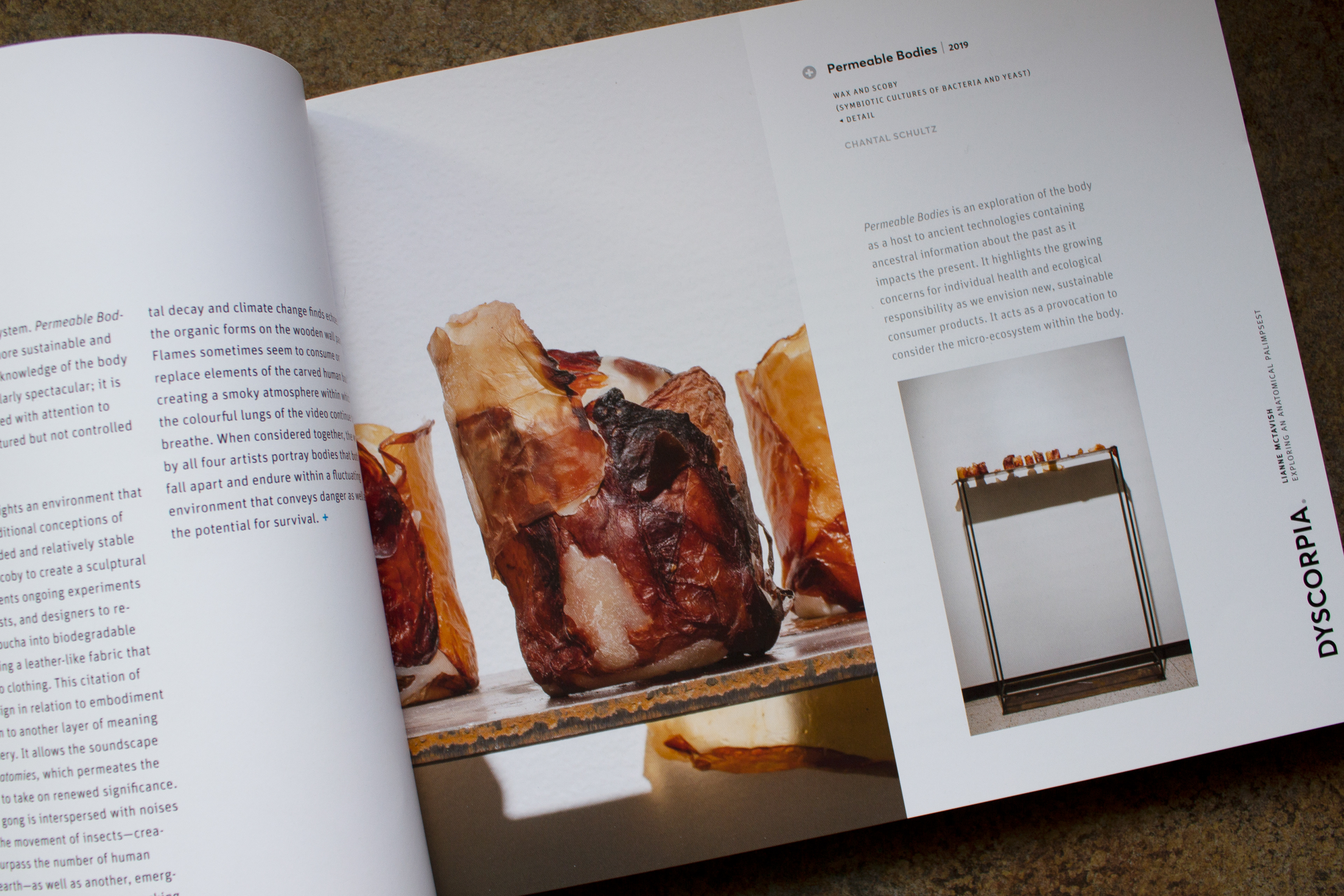

Another art work stands quietly against the far wall, separated from and yet in dialogue with “Evolving Anatomies.” Created by Chantel Schultz, “Permeable Bodies” consists of small translucent ochre and charcoal-coloured vessels placed atop a narrow metal platform supported by slender legs. Displayed at the eye level of visitors, the containers are roughly formed, as if folded together from a thick, fleshly material. Some appear to be charred and melting like wax, alluding to the votive candles lit in memory of deceased relatives in Catholic chapels. The vessels in “Permeable Bodies” nevertheless have an active presence, seeming to move and expand at will, in defiance of human efforts to shape them. One even folds over the corner of the platform, threatening to drip on the floor and gradually inhabit the space, like a plant or other organic form.

This suggestion of a burgeoning and fertile substance is reinforced by its scent, at once faintly sweet and acrid. This fragrance stems from the outer layer of the vessels, which the artist made by mixing scoby, a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast, with a fermented tea known as kombucha and sugar. Schultz cultured, dried, and then molded this dynamic and pliable substance. Her methods were inspired by the human microbiome, an invisibly crucial entity comprised of trillions of bacteria and microbes that live within and on the human body: less than half of these cells are human. By including generative bacteria in her art work, Schultz points beyond a strictly human body. Her materials extend the project of “Evolving Anatomies” into the current and future project of anatomical research, which increasingly frames the human body as one part—probably not the most important part—of a broader ecosystem. “Permeable Bodies” indicates that this more sustainable and less ego-centric future knowledge of the body is not flashy or particularly spectacular; it is thoughtfully constructed with attention to interdependence, nurtured but not controlled by human actors.

Schultz’s work highlights an environment that extends beyond traditional conceptions of the body as a bounded and relatively stable entity. Her use of scoby to create a sculptural material complements ongoing experiments by scientists, artists, and designers to reshape dried kombucha into biodegradable products, including a leather-like fabric that can be made into clothing. This citation of sustainable design in relation to embodiment draws attention to another layer of meaning within the gallery. It allows the soundscape of “Evolving Anatomies,” which permeates the entire space, to take on renewed significance. The periodic gong is interspersed with noises that mimic the movement of insects—creatures that surpass the number of human beings on earth—as well as another, emerging reference: is it the sound of ice cracking and melting? This indication of environmental decay and climate change finds echoes in the organic forms on the wooden wall panels. Flames sometimes seem to consume or replace elements of the carved human bodies, creating a smoky atmosphere within which the colourful lungs of the video continue to breathe. When considered together, the work by all four artists portray bodies that both fall apart and endure within a fluctuating environment that conveys danger as well as the potential for survival.